DNA

Saturday, February 5, 2011

Overview of biological functions

DNA usually occurs as linear chromosomes in eukaryotes, and circular chromosomes in prokaryotes. The set of chromosomes in a cell makes up its genome; the human genome has approximately 3 billion base pairs of DNA arranged into 46 chromosomes. The information carried by DNA is held in the sequence of pieces of DNA called genes. Transmission of genetic information in genes is achieved via complementary base pairing. For example, in transcription, when a cell uses the information in a gene, the DNA sequence is copied into a complementary RNA sequence through the attraction between the DNA and the correct RNA nucleotides. Usually, this RNA copy is then used to make a matching protein sequence in a process called translation which depends on the same interaction between RNA nucleotides. Alternatively, a cell may simply copy its genetic information in a process called DNA replication. The details of these functions are covered in other articles; here we focus on the interactions between DNA and other molecules that mediate the function of the genome.

DNA damage

Benzopyrene, the major mutagen in tobacco smoke, in an adduct to DNA

DNA can be damaged by many different sorts of mutagens, which change the DNA sequence. Mutagens include oxidizing agents, alkylating agents and also high-energy electromagnetic radiation such as ultraviolet light and X-rays. The type of DNA damage produced depends on the type of mutagen. For example, UV light can damage DNA by producing thymine dimers, which are cross-links between pyrimidine bases. On the other hand, oxidants such as free radicals or hydrogen peroxide produce multiple forms of damage, including base modifications, particularly of guanosine, and double-strand breaks. In each human cell, about 500 bases suffer oxidative damage per day. Of these oxidative lesions, the most dangerous are double-strand breaks, as these are difficult to repair and can produce point mutations, insertions and deletions from the DNA sequence, as well as chromosomal translocations.Many mutagens fit into the space between two adjacent base pairs, this is called intercalating. Most intercalators are aromatic and planar molecules, and include ethidium, daunomycin, doxorubicin and thalidomide. In order for an intercalator to fit between base pairs, the bases must separate, distorting the DNA strands by unwinding of the double helix. This inhibits both transcription and DNA replication, causing toxicity and mutations. As a result, DNA intercalators are often carcinogens, and benzopyrene diol epoxide, acridines, aflatoxin and ethidium bromide are well-known examples. Nevertheless, due to their ability to inhibit DNA transcription and replication, these toxins are also used in chemotherapy to inhibit rapidly-growing cancer cells.

Base modifications

The expression of genes is influenced by how the DNA ia packaged in chromosomes, in a structure called chromatin. Base modifications can be involved in packaging, with regions of that have low or no gene expression usually containing high levels of methylation of cytosine bases. For example, cytosine methylation, produces 5-methylcytosine, which is important for X-chromosome inactivation. The average level of methylation varies between organisms - the worm Caenorhabditis elegans lacks cytosine methylation, while vertebrates have higher levels, with up to 1% of their DNA containing 5-methylcytosine. Despite the importance of 5-methylcytosine, it can deaminate to leave a thymine base, methylated cytosines are therefore particularly prone to mutations. Other base modifications include adenine methylation in bacteria and the glycosylation of uracil to produce the "J-base" in kinetoplastids

Chemical modifications

| cytosine | 5-methylcytosine | thymine |

Structure of cytosine with and without the 5-methyl group. After deamination the 5-methylcytosine has the same structure as thymine

Quadruplex structures

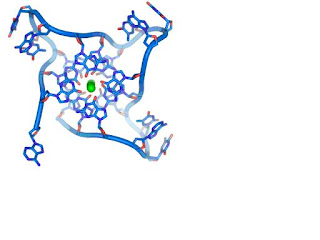

At the ends of the linear chromosomes are specialized regions of DNA called telomeres. The main function of these regions is to allow the cell to replicate chromosome ends using the enzyme telomerase, as the enzymes that normally replicate DNA cannot copy the extreme 3′ ends of chromosomes. These specialized chromosome caps also help protect the DNA ends, and stop the DNA repair systems in the cell from treating them as damage to be corrected. In human cells, telomeres are usually lengths of single-stranded DNA containing several thousand repeats of a simple TTAGGG sequence.

These guanine-rich sequences may stabilize chromosome ends by forming structures of stacked sets of four-base units, rather than the usual base pairs found in other DNA molecules. Here, four guanine bases form a flat plate and these flat four-base units then stack on top of each other, to form a stable G-quadruplex structure. These structures are stabilized by hydrogen bonding between the edges of the bases and chelation of a metal ion in the centre of each four-base unit. Other structures can also be formed, with the central set of four bases coming from either a single strand folded around the bases, or several different parallel strands, each contributing one base to the central structure.

In addition to these stacked structures, telomeres also form large loop structures called telomere loops, or T-loops. Here, the single-stranded DNA curls around in a long circle stabilized by telomere-binding proteins. At the very end of the T-loop, the single-stranded telomere DNA is held onto a region of double-stranded DNA by the telomere strand disrupting the double-helical DNA and base pairing to one of the two strands. This triple-stranded structure is called a displacement loop or D-loop.

Alternative double-helical structures

DNA exists in many possible conformations. However, only A-DNA, B-DNA, and Z-DNA have been observed in organisms. Which conformation DNA adopts depends on the sequence of the DNA, the amount and direction of supercoiling, chemical modifications of the bases and also solution conditions, such as the concentration of metal ions and polyamines. Of these three conformations, the "B" form described above is most common under the conditions found in cells. The two alternative double-helical forms of DNA differ in their geometry and dimensions.

The A form is a wider right-handed spiral, with a shallow, wide minor groove and a narrower, deeper major groove. The A form occurs under non-physiological conditions in dehydrated samples of DNA, while in the cell it may be produced in hybrid pairings of DNA and RNA strands, as well as in enzyme-DNA complexes. Segments of DNA where the bases have been chemically-modified by methylation may undergo a larger change in conformation and adopt the Z form. Here, the strands turn about the helical axis in a left-handed spiral, the opposite of the more common B form. These unusual structures can be recognized by specific Z-DNA binding proteins and may be involved in the regulation of transcription.

Supercoiling

DNA can be twisted like a rope in a process called DNA supercoiling. With DNA in its "relaxed" state, a strand usually circles the axis of the double helix once every 10.4 base pairs, but if the DNA is twisted the strands become more tightly or more loosely wound. If the DNA is twisted in the direction of the helix, this is positive supercoiling, and the bases are held more tightly together. If they are twisted in the opposite direction, this is negative supercoiling, and the bases come apart more easily. In nature, most DNA has slight negative supercoiling that is introduced by enzymes called topoisomerases. These enzymes are also needed to relieve the twisting stresses introduced into DNA strands during processes such as transcription and DNA replication

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)